![]() My brain tumor story began in late 2006, when I suffered a series of debilitating seizures. Such symptoms would typically result in emergency treatment, but my case was complicated by the fact that I had suffered from epilepsy since childhood. It had been kept under control with medication, and by 2006 I had been seizure-free for years. Nonetheless, my physicians attributed these new seizures to my old epilepsy condition. Medication was increased but the convulsions got progressively worse. One day in early 2007, I awoke to find the right half of my face paralyzed, with generalized stiffness on the right side of my body. My wife took me to the emergency room. I was given a CAT scan, which showed a large tumor in my left frontal lobe along the motor strip.

My brain tumor story began in late 2006, when I suffered a series of debilitating seizures. Such symptoms would typically result in emergency treatment, but my case was complicated by the fact that I had suffered from epilepsy since childhood. It had been kept under control with medication, and by 2006 I had been seizure-free for years. Nonetheless, my physicians attributed these new seizures to my old epilepsy condition. Medication was increased but the convulsions got progressively worse. One day in early 2007, I awoke to find the right half of my face paralyzed, with generalized stiffness on the right side of my body. My wife took me to the emergency room. I was given a CAT scan, which showed a large tumor in my left frontal lobe along the motor strip.

![]() On February 9, 2007 I had a craniotomy at the Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, in Milan Italy. The operation was considered a total resection. Before the operation, the surgeon had requested my permission to be as aggressive as possible (permission which I granted), but warned me to be prepared for deficits, including the possibility of hemiplegia. In reality, my only post-operative deficits were similar to the pre-operative ones: facial paralysis, right-side weakness, and minor aphasia. These problems gradually improved in the weeks, months and years following the operation.

On February 9, 2007 I had a craniotomy at the Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, in Milan Italy. The operation was considered a total resection. Before the operation, the surgeon had requested my permission to be as aggressive as possible (permission which I granted), but warned me to be prepared for deficits, including the possibility of hemiplegia. In reality, my only post-operative deficits were similar to the pre-operative ones: facial paralysis, right-side weakness, and minor aphasia. These problems gradually improved in the weeks, months and years following the operation.

![]() I was sent home to await the pathology report, which arrived within a few days. The diagnosis was a glioblastoma multiforme, a conclusion confirmed by two other laboratories, which independently analyzed the tumor tissue on paraffin slides. I received the usual prognosis for this disease: Almost certain recurrence within a year, with very slim odds of surviving more than three years. Molecular testing reported that my tumor's MGMT status was non-methylated, a prognostic factor working against me.

I was sent home to await the pathology report, which arrived within a few days. The diagnosis was a glioblastoma multiforme, a conclusion confirmed by two other laboratories, which independently analyzed the tumor tissue on paraffin slides. I received the usual prognosis for this disease: Almost certain recurrence within a year, with very slim odds of surviving more than three years. Molecular testing reported that my tumor's MGMT status was non-methylated, a prognostic factor working against me.

![]() I sought out therapeutic options. At that time (2007) in Italy, the current "gold standard" therapy was not widely applied. The center where my operation was performed offered me the following: six monthly rounds of chemotherapy (temozolomide plus cisplatin), with radiation to take place after the second round, administered in hyperfractionated doses over a two-week period. When I questioned the rationale behind the proposed plan, I was told that they had had some initial success with it, and more to the point, it was the only option they were offering to GBM patients at that time. I decided to look elsewhere for therapy. My real glioblastoma story starts at this point.

I sought out therapeutic options. At that time (2007) in Italy, the current "gold standard" therapy was not widely applied. The center where my operation was performed offered me the following: six monthly rounds of chemotherapy (temozolomide plus cisplatin), with radiation to take place after the second round, administered in hyperfractionated doses over a two-week period. When I questioned the rationale behind the proposed plan, I was told that they had had some initial success with it, and more to the point, it was the only option they were offering to GBM patients at that time. I decided to look elsewhere for therapy. My real glioblastoma story starts at this point.

![]() By that time I had read the famous paper by Stupp et. al. "Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma", which showed some benefit for concurrent administration of daily temozolomide during the six week period of radiotherapy. This was already a default standard in the United States and elsewhere, but was not widely available here. We spent a tense week calling all over Italy, trying to find a hospital which would offer this therapy. The physicians we contacted were aware of the relevant study results, but few were in a position to offer it. We finally found two radiation oncologists in Pisa who had participated in an earlier Phase II study of the Stupp protocol, and were willing to offer this therapy to me. I got started immediately.

By that time I had read the famous paper by Stupp et. al. "Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma", which showed some benefit for concurrent administration of daily temozolomide during the six week period of radiotherapy. This was already a default standard in the United States and elsewhere, but was not widely available here. We spent a tense week calling all over Italy, trying to find a hospital which would offer this therapy. The physicians we contacted were aware of the relevant study results, but few were in a position to offer it. We finally found two radiation oncologists in Pisa who had participated in an earlier Phase II study of the Stupp protocol, and were willing to offer this therapy to me. I got started immediately.

![]() Even before the radiation phase, I had begun to read everything I could find about brain tumors, searching for ways to improve my survival probabilities. PubMed was an invaluable resource. At some point I stumbled on the Virtual Trials site, which provided me with substantial information about my illness. I found Ben Williams' story to be particularly interesting. The logic behind his treatment approach was compelling. I read Ben's book and his yearly update, which led to an exchange of email, followed by several telephone conversations. Throughout this ordeal Ben has been an invaluable source of knowledge and support for me, as he has been for many other patients.

Even before the radiation phase, I had begun to read everything I could find about brain tumors, searching for ways to improve my survival probabilities. PubMed was an invaluable resource. At some point I stumbled on the Virtual Trials site, which provided me with substantial information about my illness. I found Ben Williams' story to be particularly interesting. The logic behind his treatment approach was compelling. I read Ben's book and his yearly update, which led to an exchange of email, followed by several telephone conversations. Throughout this ordeal Ben has been an invaluable source of knowledge and support for me, as he has been for many other patients.

![]() I was in the fortunate position of having had a total resection. However, I was aware that the odds of recurrence within one year were extremely high, and that a recurrent tumor is more problematic to control, due to its acquired resistance to first-line therapies. My goal, therefore, became that of postponing a recurrence for as long possible, and to do so via all means at my disposal. The approach was along the lines of that advocated by Ben Williams: to simultaneously block multiple tumor growth mechanisms, using a "cocktail" of agents which had shown some evidence of efficacy against GBMs or other types of cancer.

I was in the fortunate position of having had a total resection. However, I was aware that the odds of recurrence within one year were extremely high, and that a recurrent tumor is more problematic to control, due to its acquired resistance to first-line therapies. My goal, therefore, became that of postponing a recurrence for as long possible, and to do so via all means at my disposal. The approach was along the lines of that advocated by Ben Williams: to simultaneously block multiple tumor growth mechanisms, using a "cocktail" of agents which had shown some evidence of efficacy against GBMs or other types of cancer.

![]() During the six weeks of radiation, I had ample time to start planning for the next treatment phase. My oncologist proposed eight monthly rounds of temozolomide on the standard 5/23 schedule. I had read that this schedule provided limited benefit for someone like me, whose tumor MGMT status was unmethylated. But there were were some positive reports of experiments using a low-dose, daily (metronomic) schedule, in which MGMT methylation status had less of an effect on patient outcomes. Based on this argument, I lobbied my physicians to try the metronomic schedule, and they said that they would consider it.

In 2007 the drug Avastin was becoming popular as an experimental treatment for recurrent glioblastoma. Based on positive results from various early studies, I wanted to add Avastin to the proposed metronomic therapy for temozolomide. This highly anti-angiogenic approach was attractive to me, because it had the potential to forestall recurrence by delaying re-vascularization in the tumor area. I discussed the idea with some prominent neuro-oncologists around the world, and received encouragement from many quarters. Physicians at Duke were particularly enthusiastic, and generously offered to write letters of support for my plan. With the help of a researcher in the Netherlands, I drafted a proposal for my Avastin/metronomic TMZ protocol, which I presented to the oncologists in Pisa. They were interested in seeing whether such a protocol could work in a case like mine. Provided that I sign a consent form, they were willing to send the proposal through the hospital's internal review board, which approved it as a one-person experiment.

During the six weeks of radiation, I had ample time to start planning for the next treatment phase. My oncologist proposed eight monthly rounds of temozolomide on the standard 5/23 schedule. I had read that this schedule provided limited benefit for someone like me, whose tumor MGMT status was unmethylated. But there were were some positive reports of experiments using a low-dose, daily (metronomic) schedule, in which MGMT methylation status had less of an effect on patient outcomes. Based on this argument, I lobbied my physicians to try the metronomic schedule, and they said that they would consider it.

In 2007 the drug Avastin was becoming popular as an experimental treatment for recurrent glioblastoma. Based on positive results from various early studies, I wanted to add Avastin to the proposed metronomic therapy for temozolomide. This highly anti-angiogenic approach was attractive to me, because it had the potential to forestall recurrence by delaying re-vascularization in the tumor area. I discussed the idea with some prominent neuro-oncologists around the world, and received encouragement from many quarters. Physicians at Duke were particularly enthusiastic, and generously offered to write letters of support for my plan. With the help of a researcher in the Netherlands, I drafted a proposal for my Avastin/metronomic TMZ protocol, which I presented to the oncologists in Pisa. They were interested in seeing whether such a protocol could work in a case like mine. Provided that I sign a consent form, they were willing to send the proposal through the hospital's internal review board, which approved it as a one-person experiment.

![]() Things were looking good, but I wanted to pursue a more aggressive strategy. I added chloroquine to the therapy, after reading papers which showed that it improved results for chemotherapy. I likewise included verapamil, which could potentially inhibit extrusion of chemotherapy agents from cancer cells, and help prevent multi-drug resistance. Another addition was aspirin (200mg/day), mainly as a prophylactic against blood clots from Avastin, but which had potential anti-cancer benefits in its own right. The drug Celebrex was also included early on, due to promising results from small clinical trials for brain tumors and other cancers. Before going further, I compiled a list of 60-plus agents that could potentially contribute to the therapy, which fell into three categories: (a) they had shown efficacy against some form of cancer, either in clinical or pre-clinical settings; (b) had shown to be synergistic with chemotherapy or other substances already in my therapy; or (c) they had demonstrated positive effects in building up the immune system. The list was eventually refined to 27 substances, many of which were natural supplements, for example, green tea extract, fermented papaya extract, omega-3 fish oils, resveratrol, melatonin, mushroom extracts, selenium, and so on.

Things were looking good, but I wanted to pursue a more aggressive strategy. I added chloroquine to the therapy, after reading papers which showed that it improved results for chemotherapy. I likewise included verapamil, which could potentially inhibit extrusion of chemotherapy agents from cancer cells, and help prevent multi-drug resistance. Another addition was aspirin (200mg/day), mainly as a prophylactic against blood clots from Avastin, but which had potential anti-cancer benefits in its own right. The drug Celebrex was also included early on, due to promising results from small clinical trials for brain tumors and other cancers. Before going further, I compiled a list of 60-plus agents that could potentially contribute to the therapy, which fell into three categories: (a) they had shown efficacy against some form of cancer, either in clinical or pre-clinical settings; (b) had shown to be synergistic with chemotherapy or other substances already in my therapy; or (c) they had demonstrated positive effects in building up the immune system. The list was eventually refined to 27 substances, many of which were natural supplements, for example, green tea extract, fermented papaya extract, omega-3 fish oils, resveratrol, melatonin, mushroom extracts, selenium, and so on.

![]() I may have taken a few ideas to extremes. For example, I drank over 2 liters of green tea per day, which eventually became my primary source of liquid consumption. (I was trying to sustain concentrations achieved in laboratory mice, reported in a successful study for prostate cancer.) Similarly, for the first year of therapy, I attempted to maximize my intake of curcumin (turmeric) and cayenne pepper (capsicum), based on pre-clinical studies showing some promise for these substances. But I used these spices in foods which were totally unsuited for them, resulting in some rather humorous culinary failures. It is questionable whether these experiments did me any good. However, I was fanatically dedicated to incorporating any and all tactics that could contribute, albeit marginally, to the efficacy of my therapy – provided the overall result was not toxic.

I may have taken a few ideas to extremes. For example, I drank over 2 liters of green tea per day, which eventually became my primary source of liquid consumption. (I was trying to sustain concentrations achieved in laboratory mice, reported in a successful study for prostate cancer.) Similarly, for the first year of therapy, I attempted to maximize my intake of curcumin (turmeric) and cayenne pepper (capsicum), based on pre-clinical studies showing some promise for these substances. But I used these spices in foods which were totally unsuited for them, resulting in some rather humorous culinary failures. It is questionable whether these experiments did me any good. However, I was fanatically dedicated to incorporating any and all tactics that could contribute, albeit marginally, to the efficacy of my therapy – provided the overall result was not toxic.

![]() With minor exceptions, scans have been clear since the summer of 2007. There were a few scares during the first two years, with images showing small degrees of enhancement in and around the tumor cavity. But these abnormalities were likely due to radiation damage, and in any case they disappeared over time. I now get yearly MRIs, and no changes have been noted for many years.

With minor exceptions, scans have been clear since the summer of 2007. There were a few scares during the first two years, with images showing small degrees of enhancement in and around the tumor cavity. But these abnormalities were likely due to radiation damage, and in any case they disappeared over time. I now get yearly MRIs, and no changes have been noted for many years.

![]() Thanks for reading my story. Note that if I had to go through this again, I would alter many of the details in my treatment plan, based on discoveries made in years subsequent to my diagnosis. I would not, however, change my treatment approach, that is, to aggressively battle the tumor using multiple agents simultaneously, thereby inhibiting as many growth pathways as possible. At of this writing (2014), I still believe that this is the most effective way to treat a glioblastoma. For other patients, I would advise to get as educated as possible about this disease, and to participate in formulating your treatment plan, to the best of your ability. Make your voice heard. Never be afraid to ask questions or offer suggestions, based on what you have learned from other sources (including other patients). If you feel like your input is being ignored, then find another physician who will listen to you.

Thanks for reading my story. Note that if I had to go through this again, I would alter many of the details in my treatment plan, based on discoveries made in years subsequent to my diagnosis. I would not, however, change my treatment approach, that is, to aggressively battle the tumor using multiple agents simultaneously, thereby inhibiting as many growth pathways as possible. At of this writing (2014), I still believe that this is the most effective way to treat a glioblastoma. For other patients, I would advise to get as educated as possible about this disease, and to participate in formulating your treatment plan, to the best of your ability. Make your voice heard. Never be afraid to ask questions or offer suggestions, based on what you have learned from other sources (including other patients). If you feel like your input is being ignored, then find another physician who will listen to you.

![]() It has been over nine years since my diagnosis, without any signs of recurrence. I currently get an MRI every year, and will switch to every other year after I've passed the 10 year survival point. I do suffer some long-term effects from my therapy (mainly radiation), the most annoying of which is chronic xerostomia (dry mouth). The good news is that my previous epilepsy condition has disappeared. Prior to my surgery, I suffered at least 8 seizures per year, and I had only two seizures since the craniotomy in 2007 (the last one in 2012).

It has been over nine years since my diagnosis, without any signs of recurrence. I currently get an MRI every year, and will switch to every other year after I've passed the 10 year survival point. I do suffer some long-term effects from my therapy (mainly radiation), the most annoying of which is chronic xerostomia (dry mouth). The good news is that my previous epilepsy condition has disappeared. Prior to my surgery, I suffered at least 8 seizures per year, and I had only two seizures since the craniotomy in 2007 (the last one in 2012).

![]() It has been over 13 years since my diagnosis, still without any sign of a recurrence. I have been living in the US for a couple of years, but I still spend as much time as I can in Italy. I am so grateful to have been treated there, where I received a treatment protocol that would have been impossible to organize in the US. Also the level of care in general far superior in Italy to the US, and patients will pay next to nothing for their treatment - and hence they need not worry about the cost of that treatment. I frankly do not understand why Americans resist having a national health service like that in the rest of the world, but I suppose this is not the place for such a discussion.

It has been over 13 years since my diagnosis, still without any sign of a recurrence. I have been living in the US for a couple of years, but I still spend as much time as I can in Italy. I am so grateful to have been treated there, where I received a treatment protocol that would have been impossible to organize in the US. Also the level of care in general far superior in Italy to the US, and patients will pay next to nothing for their treatment - and hence they need not worry about the cost of that treatment. I frankly do not understand why Americans resist having a national health service like that in the rest of the world, but I suppose this is not the place for such a discussion.

![]() I have suffered a few long-term effects of the treatments I received. After the therapy I started to suffer from xerostomia and hypothyroidism. Also some bone weakening occurred, and I developed osteopenia. But all of this is manageable, and after all, is much better than what happens to most GBM patients.

I have suffered a few long-term effects of the treatments I received. After the therapy I started to suffer from xerostomia and hypothyroidism. Also some bone weakening occurred, and I developed osteopenia. But all of this is manageable, and after all, is much better than what happens to most GBM patients.

![]() Unfortunately, since my illness in 2007, there has been little improvement in outcomes for high grade brain tumors, once they are diagnosed. Fortunately they are now diagnosed a bit earlier, since physicians do have greater awareness of brain tumors, and are more likely to correlate patient symptoms with a potential tumor, and hence order the MRI.

Unfortunately, since my illness in 2007, there has been little improvement in outcomes for high grade brain tumors, once they are diagnosed. Fortunately they are now diagnosed a bit earlier, since physicians do have greater awareness of brain tumors, and are more likely to correlate patient symptoms with a potential tumor, and hence order the MRI.

![]() I am still a strong advocate of combination therapies for these tumors. There has been some acceptance of this approach in medical circles, but not nearly enough.

I am still a strong advocate of combination therapies for these tumors. There has been some acceptance of this approach in medical circles, but not nearly enough.

![]() I am frequently contacted by GBM patients, and try to give them the best advice possible, within my limited qualifications. If you do contact me, please be patient. I cannot answer all my mail immediately, but I will answer it.

I am frequently contacted by GBM patients, and try to give them the best advice possible, within my limited qualifications. If you do contact me, please be patient. I cannot answer all my mail immediately, but I will answer it.

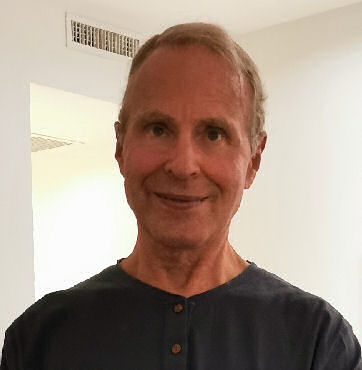

![]() I include a recent picture taken in Rome, after a few weeks in Cabo Verde - tanned (even burnt), happy and very much alive.

I include a recent picture taken in Rome, after a few weeks in Cabo Verde - tanned (even burnt), happy and very much alive.

![]() There are no changes in my condition since the last update, and my GBM saga is becoming a distant memory. While a glioblastoma is never curable, I like to consider myself in permanent remission. As for work, I have always had the advantage of being able to conduct my business online, and have never missed a day of work, save a few days after my surgery. And I am now using that advantage to travel six months out of the year. I am writing this update from the beach in Santa Marta, Colombia. I don't think I will ever "retire", since retirement can't be any better than this.

There are no changes in my condition since the last update, and my GBM saga is becoming a distant memory. While a glioblastoma is never curable, I like to consider myself in permanent remission. As for work, I have always had the advantage of being able to conduct my business online, and have never missed a day of work, save a few days after my surgery. And I am now using that advantage to travel six months out of the year. I am writing this update from the beach in Santa Marta, Colombia. I don't think I will ever "retire", since retirement can't be any better than this.

![]() My only post-GBM complaint is that my balance frequently gives me problems, but that is such a small deficit compared to what could have happened to me.

My only post-GBM complaint is that my balance frequently gives me problems, but that is such a small deficit compared to what could have happened to me.